TESS Finds a Planet That Takes 482 Days to Orbit, the Widest it’s Seen so Far

By Evan Gough

We’re rapidly learning that our Solar System, so familiar to us all, does not represent normal.

A couple of decades ago, we knew very little about other solar systems. Astronomers had discovered only a handful of exoplanets, especially around pulsars. But that all changed in the last few years.

Exoplanet-hunting telescopes like Kepler and TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) have shown us that our Solar System is a bit of an anomaly. Over 80% of the exoplanets found by Kepler and TESS orbit their stars in fewer than 50 days. That’s quicker than Mercury’s 88-day orbit. (How weird would it be if most of the planets in our Solar System were inside Mercury’s orbit?)

Now, TESS has found a planet on the other end of the orbital spectrum. Rather than adhering to an intimate orbit that keeps it near its star, this new planet has the widest orbit yet found by TESS. It takes 482 days to orbit.

That may not sound like a lot, considering our Solar System’s furthest planet, Neptune, takes 165 years to orbit the Sun. But because of the way TESS works, finding planets on wide orbits is challenging for the spacecraft.

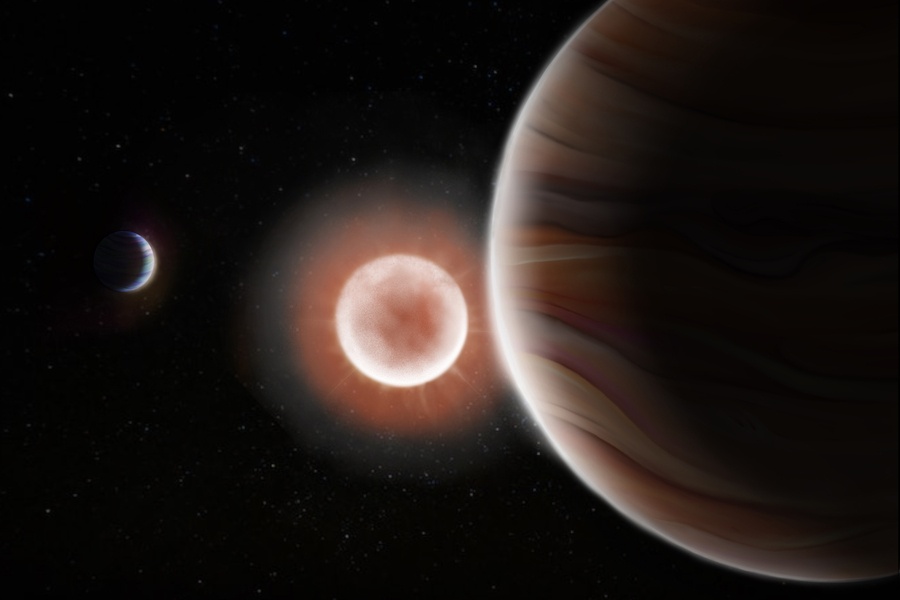

The planet’s name is TOI-4600c. A team of astronomers from MIT and other institutions detected the planet—and a sibling—around a star 815 light-years away. They published their results in a paper titled “TOI-4600 b and c: Two Long-period Giant Planets Orbiting an Early K Dwarf.” The paper is available in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, and the lead author is Ismael Mireles, a graduate student at the University of New Mexico.

TESS uses the transit method to detect planets, so that means long-period planets are more difficult to detect than short-period planets. If a planet like TOI-4600c takes 482 days to orbit its star, then TESS has to monitor the star for at least 483 days—and probably much longer than that—to catch two transits. Two transits are necessary before they indicate the presence of a possible planet. One transit isn’t enough.

But detecting exoplanets is just the beginning. Astronomers also want to characterize exoplanets and understand their history, formation, composition, density, and anything else they can learn about them. That’s easier with planets closer to their stars, but much harder for planets on wide orbits. Consequently, we know more about close-in planets than we do about wide-orbit planets.

A 482-day orbit is long in exoplanet terms. In terms of our own Solar System, it puts TOI-4600c in between Earth’s 365-day orbit and Mars’ 687-day orbit, which isn’t very remarkable. But this new planet is much different than Earth and Mars.

TOI-4600c is cold. In fact, it’s one of the coldest exoplanets yet detected at -117 Fahrenheit (-83 C, 190 K.) Both this planet and its sibling, TOI-4600b, are gas giants, though 4600c is likely an ice giant. This is unusual in exoplanet science since so many of the planets we find are Hot Jupiters. This pair likely bridges the gap between the Hot Jupiters alien to our Solar System and the long-period ice giants like Jupiter and Saturn that we know so well.

Astronomers want to know how our own Solar System fits in the grand scheme of other solar systems. That’s why finding planets like these, which are outliers in terms of exoplanets, is important.

Katharine Hesse is a technical staff member at MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research and one of the paper’s co-authors. “These longer-period systems are a comparatively unexplored range,” said Hesse. “As we’re trying to see where our solar system falls in comparison to the other systems we’ve found out there, we really need these more edge-case examples to better understand that comparison. Because a lot of systems we have found don’t look anything like our solar system.”

Here’s how TESS works: It examines a patch of sky for 30 days at a time before examining the next patch. It gathers data continuously during these 30 periods, and the data goes through an automated pipeline that uses algorithms to search for planets. When the algorithm identifies a possible planet, it becomes a TESS Object of Interest (TOI,) hence the newly-found planet’s name: TOI-4600c.

This new planet was detected in 2020 when the algorithm found a possible transit near the constellation Draco. At that point, it was just a candidate planet based on a single transit.

Then the data was sent to a particular team called the TESS Single Transit Planet Candidate Working Group. This group examines single-transit events to try to determine if the event is a longer-period planet. “For missions like TESS, where it only looks at each region of the sky for 30 days, you really need to stack up the number of observations to be able to get enough data to find planets with orbits longer than a month,” Hesse said.

The Working Group got busy looking for other transits of the same pair of planets that might be present in other TESS data. They found three more transits and confirmed the inner planet, TOI-4600b. The team also had a happy accident when examining the data. There was another transit that was out of sync with those of the inner planet. It could’ve been another star transiting TOI-4600, or it could’ve been an additional planet.

The only way to confirm the other transit as a planet was with more transits. Lead author Mireles joined the effort in 2021 and looked for more TESS observations that could provide confirmation.

“With each sector of data that came down, I would look to see if there was a second transit, and in the first five sectors, there wasn’t,” Mireles recalls. “Then, in July of last year, we saw something.”

There were two more separate transits, and they presented a bit of a mystery.

One of them was in the same 82-day cycle as the preceding out-of-sync transit for the suspected long-period planet. The second one was detected 964 days after the out-of-sync transit. But they were similar in the amount of starlight they blocked. That was a strong indication that the same object caused both transits. That object had to be on either a 482-day orbit or an orbit double that length, 964 days.

After more modelling, the team settled on a single planet on a 482-day orbit to explain these transits.

That means that the star hosted two long-period planets. (While the inner planet, TOI-4600b, has an orbital period of 82.69 days, that’s long for an exoplanet.)

Follow-up observations with ground-based optical telescopes followed, and the researchers concluded that 4600b is likely a warm, Jupiter-like gas giant, or what the researchers call a temperate sub-Saturn. 4600c is likely an ice giant, also called a cold Saturn. 4600b is about 6.8 Earth radii, and 4600c is about 9.4 Earth radii.

There’s uncertainty regarding their orbits, but future radial velocity measurements might resolve them. Those observations will reveal more about the planets’ formation and evolution.

This discovery breaks the mould for exoplanet discoveries since finding two giant planets in one exosystem is rare. There are fewer than three dozen multi-transiting with a warm Jupiter/Saturn like this system, and TOI 4600c is both the coolest transiting planet and the widest-orbiting planet in the sample. As an outlier, it could teach us a lot about how solar systems form and evolve.

“A rarely seen system with two such types of planets may play a significant role in advancing our understanding of planet formation and evolution,” the authors write in their paper. Not only that, but both of these planets are amenable to atmospheric study by the JWST.

“It’s relatively rare that we see two giant planets in a system,” Hesse said. “We’re used to seeing hot Jupiters that are close in to their stars, and we usually don’t find companions to them, let alone giant companions. This system is a more unique configuration.”

The TOI 4600 system may hold other planets if the distance between these two is any indication. 4600b and 4600c are about the same distance apart as Mercury and Mars. A gap that large would be unexpected.

“We want to see if there’s evidence for more planets,” Mireles says. “There’s definitely a lot of room for potential planets, either closer in, or further out. And we show that TESS is capable of finding both warm and cold Jupiters.”

The post TESS Finds a Planet That Takes 482 Days to Orbit, the Widest it’s Seen so Far appeared first on Universe Today.

September 6, 2023 at 11:35PM

via Universe Today read more...

Post a Comment