SpaceX and OneWeb spar over satellite close approach

By Jeff Foust

ORLANDO — An alleged close approach between satellites from OneWeb and SpaceX led to a meeting between the companies and the Federal Communications Commission, but the companies don’t completely agree on what resulted from that discussion.

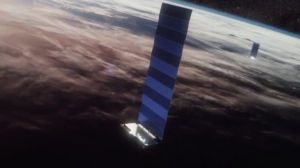

OneWeb officials said in early April that they had to move one of their satellites to avoid a close approach with a SpaceX Starlink satellite. The OneWeb satellite, OneWeb-0178, was one of 36 satellites launched March 25 on a Soyuz rocket from the Vostochny Cosmodrome in Russia. As the spacecraft was raising its orbit, it was projected to come close to Starlink-1546, a satellite launched in September 2020 and currently in an orbit of about 450 kilometers.

OneWeb said that initial estimates of the potential conjunction provided by the U.S. Space Force’s 18th Space Control Squadron (SPCS) March 30 projected that the two satellites would come within about 60 meters of each other, with a 1.3% chance of a collision, on April 3. Chris McLaughlin, head of government affairs for OneWeb, told The Verge, which first reported about the conjunction, that SpaceX disabled the automated collision avoidance system on that Starlink satellite to allow the OneWeb satellite to maneuver safely.

McLaughlin, though, later told The Wall Street Journal that SpaceX informed the company it couldn’t do anything to avoid a collision and thus switched off the automated system on that satellite. “SpaceX has a gung-ho approach to space,” he told the newspaper, comparing Starlink satellites to electric cars produced by Tesla, which, like SpaceX, is led by Elon Musk: “They launch them and then they have to upgrade and fix them, or even replace them altogether.”

SpaceX did not publicly comment on those reports, but did arrange a meeting with both OneWeb and the FCC’s International Bureau, which regulates communications satellites. That April 20 meeting, according to a filing SpaceX made with the FCC later that day, discussed the satellite conjunction and SpaceX’s own assessment of the event.

“Despite recent reports to the contrary, the parties made clear that there was no ‘close call’ or ‘near miss,’” SpaceX stated. “SpaceX and OneWeb agreed that they had conducted a successful coordination, resulting in a positive outcome.”

SpaceX included in its filing its chronology of the conjunction, discussing email exchanges and phone calls between the companies. In one call April 2, SpaceX noted that LeoLabs, which tracks objects using its network of radars, predicted a probability of collision well below the threshold of 1-in-100,000 used to decide whether to perform a maneuver. A comparison of orbital data between OneWeb and SpaceX briefly showed a higher probability of collision, including the 1.3% chance of collision reported, but SpaceX said OneWeb acknowledged it underestimated the uncertainty in its orbital projections.

In a second call, less than two hours later, OneWeb decided it wanted to perform a collision avoidance maneuver because it could not wait for additional data. OneWeb asked SpaceX to turn off the automated collision avoidance system on Starlink-1546, which SpaceX did, and OneWeb then performed a maneuver of OneWeb-0178 on April 3.

By the time of the maneuver, though, the probability of a collision had already become insignificant based on refined orbital data. “In other words, the probability of collision was already below any threshold that required a maneuver and kept dropping,” SpaceX stated.

The actual close approach, based on data from 18 SPCS, was 1,120 meters. LeoLabs, using its own data, estimated a close approach of 1,072 meters.

“SpaceX expressed its disappointment to the Commission that OneWeb’s officials chose to publicly misstate the circumstances of the coordination,” SpaceX stated in its filing. “SpaceX was therefore grateful that OneWeb offered in the meeting with the Commission to retract its previous incorrect statements.”

OneWeb, though, has yet to make such a retraction. Contacted about the SpaceX filing, OneWeb spokesperson Katie Dowd referred SpaceNews to OneWeb’s own FCC filing on April 21, in response to the one from SpaceX.

“OneWeb made no such offer to retract any previous statements made to the press,” the company said in the filing by its legal firm, Sheppard Mullin. “OneWeb simply noted during the meeting that press coverage can sometimes be erroneous in certain respects – a fact noted by SpaceX itself when requesting the FCC meeting in the first place. OneWeb stands by its story as reported to the press.”

OneWeb added that SpaceX did not respond to requests for comment for those earlier news reports. Dowd said that OneWeb did not plan to comment further on the matter.

OneWeb did say in its filing that it found the “exchange of facts and data between the engineering teams for SpaceX and OneWeb to be outstanding” in the meeting with the FCC. “As demonstrated yesterday during the discussion, OneWeb is committed to full cooperation with SpaceX and all other satellite operators on physical coordination of satellites.”

“Coordination did not work very well”

This is not the first controversy involving a close approach between a Starlink satellite and another spacecraft. In September 2019, the European Space Agency had to maneuver its Aeolus satellite when it determined a Starlink satellite would pass too close to it. ESA complained that it had problems coordinating with SpaceX, which the company blamed on a confluence of factors that it subsequently addressed.

“This was actually indeed a close call, and coordination did not work very well,” recalled Rolf Densing, ESA director of operations, during an April 19 press briefing as part of the 8th European Conference on Space Debris.

That has since improved. “We are, ever since, in close contact with SpaceX. I must say they are very cooperative,” he said. “We have, on a bilateral basis, found a modus vivendi with close cooperation on how to avoid this ever happening again.”

This latest incident comes as SpaceX seeks permission from the FCC to modify its existing license to lower the orbits of 2,825 satellites authorized by that license from altitudes of more than 1,000 kilometers to about 550 kilometers, joining the 1,584 satellites already approved to operate in the lower orbit. SpaceX has called the proposed change a “safety upgrade” of its constellation since, at the lower orbits, satellites will have shorter lifetimes.

That proposal faces strong opposition from a number of other companies, including OneWeb, Viasat, Hughes Network Systems and Amazon, who argue that the change would have effects ranging from spectrum interference with other satellite systems to effectively making it impossible for other satellite constellations to operate in similar orbits.

Those companies, and SpaceX, have made a series of claims and counterclaims in filings attached to the FCC docket about SpaceX’s license modification. SpaceX, in its April 20 filing, argued that OneWeb used the publicity surrounding the close approach to meet with FCC commissioners, “demanding unilateral conditions placed on SpaceX’s operations.” OneWeb said on April 14 it met with one FCC commissioner, Nathan Simington, and his staff, proposing that SpaceX be required “to closely coordinate collision avoidance events with other operators and not rely solely on its automated system.”

An argument from another satellite operator appeared to make its way into the April 21 Senate confirmation hearing for Bill Nelson, the nominee for NASA administrator. “Do you think we need rules and policies to ensure that large commercial constellations are designed and operated in a way that ensures a very low aggregate collision risk level over their lifetimes?” Sen. Cynthia Lummis (R-Wyo.) asked him.

That specific terminology echoes a proposal made by Viasat to the FCC April 12 as a condition for granting SpaceX’s license modification. “SpaceX should be required to design, deploy, and operate its modified 4,408-satellite constellation so the aggregate collision risk posed by the entire constellation does not exceed a suitable limit over its 15-year license term,” Viasat proposed.

“Yes, ma’am,” Nelson replied, but then broadly discussed the general threats posed by orbital debris, including debris created by a 2007 Chinese antisatellite weapons test, rather than the risk from Starlink or other commercial constellations.

Asked by Lummis what level of risk NASA would be willing to accept from commercial space activities, Nelson called for development of active debris removal technologies to dispose of failed satellites. “If it’s dead, then there ought to be a provision for getting it down,” he said. “That’s something that’s already started and it ought to be accelerated.”

SpaceX has faced the most scrutiny for its satellite constellation, but even ESA’s Densing suggests the company is not as bad as its critics make it out to be. “It looks at first glance like Elon Musk is the evil guy, because he is polluting space,” he said. “Actually, space is there for everybody. I must say, I’m actually a bit jealous. I must congratulate him on this great idea of starting this megaconstellation.”

April 22, 2021 at 11:31PM

via SpaceNews read more...

Post a Comment