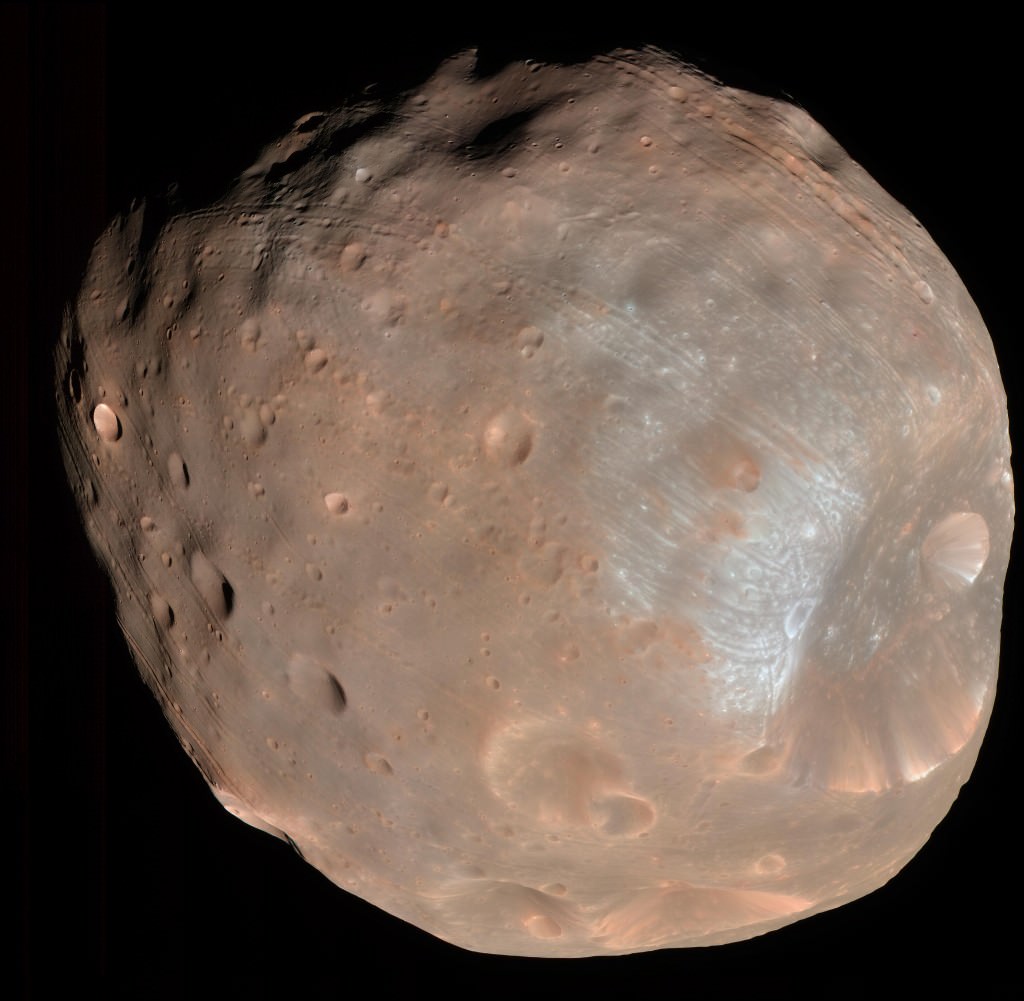

What Could We Learn From a Mission to Phobos?

By Matt Williams

According to new research that appeared in the scientific journal Nature, the larger of Mars’ two moons (Phobos) has an orbit that takes it through a stream of charged particles (ions) that flow from the Red Planet’s atmosphere. This process has been taking place for billions of years as the planet slowly lost its atmosphere, effectively establishing a record of Martian climate change on Phobos’ surface.

This research has provided yet another incentive for landing a mission on Phobos, something that has never been done successfully. In essence, this mission could gather sample data that would allow scientists to study this record more closely. In the process, they would be able to learn a great deal more about how Mars went from being a warmer world with liquid water to the extremely arid and cold environment it is today.

According to the study, which was conducted by researchers from the Space Sciences Laboratory (SSL) at the University of California at Berkeley (UC Berkeley), the Martian atmosphere began to slowly lose charged particles to space (oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and argon) ever since its magnetic field disappeared billions of years ago. This is how Mars became an extremely arid and freezing planet, with an atmosphere of less than 1% that of Earth.

Some of these ions impacted Phobos, and could therefore be preserved in the uppermost layer of the moon’s surface. As Quentin Nénon, a researcher at the Space Sciences Laboratory at UC Berkeley and the study’s lead author, explained in a recent NASA press release:

“We knew that Mars lost its atmosphere to space, and now we know that some of it ended up on Phobos. With a sample from the near side, we could see an archive of the past atmosphere of Mars in the shallow layers of grain, while deeper in the grain we could see the primitive composition of Phobos.”

Phobos has always been a source of great controversy for scientists. Like its twin, Deimos, there are many unresolved questions about where they came from. Some believe that they are large asteroids that got kicked out of the Main Belt in the past and were captured by Martian gravity. Others have suggested that they formed from the same material as Mars, while others still theorize that they formed from debris resulting from a massive impact.

Today, both of these satellites orbit their parent planet very closely and have very short orbital periods. Whereas Phobos, the closer of the two, only takes over 7 and a half hours to complete an orbit, Deimos takes about 30 hours. In addition to their origin, there are also many questions regarding their history ever since they fell into orbit around Mars (as indicated by Phobos’ many craters and linear grooves).

Because Phobos is tidally locked to Mars – meaning that it is always showing the same side to the planet – the rocks on the near side of Phobos have been exposed to ionized atmospheric particles from Mars for millennia. Since September of 2014, MAVEN has been collecting data on the Martian atmosphere to help scientists determine how and when it was lost to space, as well as provide insights into the evolution of the planet’s climate.

During its primary mission, MAVEN would cross the orbit of Phobos about five times a day, allowing it to gather data on the local ionized particles with its Suprathermal and Thermal Ion Composition (STATIC) instrument. STATIC measures the kinetic energy and velocity of incoming particles so that scientists can compute their mass. Andrew Poppe (an associate research scientist at the SSL and a co-author on the paper) and his colleagues at UC Berkeley were responsible for designing and building STATIC.

Years ago, Poppe and his associates began discussing whether samples obtained from the surface of Phobos could reveal information about early Mars. This practice, where scientists study moons to learn more about a parent body, is a long-established tradition for planetary scientists and geologists. The Moon, for example, has provided scientists with a well-preserved record of Earth’s distant past.

During the Apollo era, astronauts brought back samples of lunar rocks that provided insight into the Moon’s origin, evolution, and how smaller bodies distributed certain elements (like water) throughout the Solar System. during the Late Heavy Bombardment. This period (ca. 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago) was characterized by Earth and the other rocky planets experiencing a disproportionately high level of asteroid impacts.

To address this, Poppe and Shannon Curry (a fellow researcher at the SSL) conducted a study in 2014 where they created computer models of Mars’ moons. These provided encouraging results, confirming that Phobos and Deimos pass through heavy planetary ions escaping from Mars. In 2019, when Nénon joined SSL, he offered to look through the MAVEN mission data to see if Poppe and Curry’s model was correct.

Said Andrew Poppe, an associate research scientist at the SSL and a co-author on the paper:

“What Quentin has done is take investigations we’ve done at the Moon and at other moons of the solar system and applied the same methods to Phobos for the first time. What we’ve seen in Apollo samples is that the Moon has been patiently recording individual atoms coming from the Sun and from Earth. It’s a really cool historical record.”

After examining the MAVEN mission data collected by STATIC, Nénon and the research team were able to measure the ions in Phobos’ orbit and determine which came from Mars – as opposed to the Sun (which are generally lower in mass). From this, they concluded that Phobos’ inner side is subjected to 20 – 100 times more ions than its outer side and that these ions could be found several hundred nanometers beneath the surface.

In other words, a lander mission could set down on Phobos’ surface, dig no deeper than a fraction of the width of a hair, and obtain valuable samples to send back to Earth. This is what the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) intends to do with their upcoming Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) lander a sample-return mission that will investigate the origins of Phobos (scheduled to launch by 2024).

Nénon and his colleagues hope that the analysis of the MAVEN measurements could help JAXA determine where they should set down. “With a sample from the near side,” Nénon said, “we could see an archive of the past atmosphere of Mars in the shallow layers of grain, while deeper in the grain we could see the primitive composition of Phobos.”

If MMX were to land on the side of the moon that always faces Mars (its near side), said Nénon, the samples it returns could reveal a lot more than the origin of Phobos. They could also reveal how Mars made the transition from being a warmer, wetter planet with rivers, lakes, and an ocean on its surface to what we see there today.

This research was partially funded by the MAVEN mission (overseen by the University of Colorado Boulder and planetary scientists from NASA Goddard) and teams affiliated with NASA’s Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute (SSERVI).

The post What Could We Learn From a Mission to Phobos? appeared first on Universe Today.

February 3, 2021 at 06:14AM

via Universe Today read more...

Post a Comment